Labor of love: rigger

In July 2015, the Musilac music festival (Aix-les-Bains, France) was in full swing. Just a few hours prior to the festival, riggers were busy setting up the lighting and sound systems for the massive stage on the shores of Lake Bourget. Learn more about the intricacies of this interesting profession through an interview with Ben Mazuer, rigger.

September 18 2015

Rope access and confined space

Interview with Ben Mazuer: rigger

Ben Mazuer is a father and family man. He has worked as a rigger form almost fifteen years, all over France and abroad, even though he currently does his best to work closer to home in the Rhone-Alpes region.

Journalist by training, he is a state-certified climbing instructor and discovered the field of rigging through one of his climbing buddies.

What does rigging consist of?

What is truly unique about your profession?

"Rigging consists of raising and securing decorations, lights, and sound systems at height. The unique aspect of rigging is that we always have tight deadlines and have to work quickly. In general, we have very little time to work between setup and take down, one full day at most. Work days are long, often starting at six or seven in the morning, and setup can last until at least noon. The event in question takes place at the site, and then we dismantle everything right afterwards, usually involoving one to three hours of work, so we finish our day at midnight or even one in the morning depending on the work site. In general, we don't work in the afternoon, but sometimes the larger events require us to work straight through if the production team shows up late or if the artist plans something unique, like flying high above the stage."

How do you organize your schedule when faced with such long work days?

"We switch back and forth between long periods where we're off, and other long periods where we work non-stop. In general, we have a lot of work from October to December, a bit less work in January and February, and then ten key dates during the supposed "low" season.

We do our best to rotate each team, but sometimes scheduling is really complicated. We might need ten riggers for an auditorium job in one place, and this often happens the same day that a huge production in Lyon will require 25 riggers.

When we started, we sometimes had to work one job after the other twelve to thirteen days in a row. When you begin your day at six in the morning and you finish around after midnight, it can wear on you. Now we have a solid team and are able to rotate, to spread everyone out between work sites. For the last few years I have even been able to avoid working summer festivals since I work more than enough the rest of the year."

Is this a profession that requires lots of travel?

"The profession has two aspects. We can either work at local theaters and auditoriums that we know well, or travel with productions on tour. The two often complement each other: when we are not on tour we work locally and vice versa.

Several of us have chosen to only work locally. There are enough productions that come through the area and enough auditoriums and theaters for us to make a living. My team and I work for the Zenith in Saint Etienne, the Arena in Geneva, the Summum in Grenoble, and soon we'll be working for the Palais des Sports in Grenoble. Not too long ago we worked for Tony Garnier Hall in Lyon."

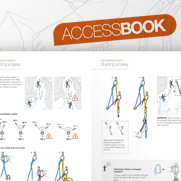

What type of equipment do you use?

"When we use layer systems or scaffolding, it's usually pretty easy to reach the rig where we hang equipment and to move around. We use the ASAP and rope access techniques. When moving horizontally, we set up lifelines or use snap hooks.

Next, we deal with the specific fastening equipment that the production company or the auditorium provides. We don’t bring raising equipment or catwalks with us to work sites."

Does that mean that you never know what type of equipment you will find at a given site?

"Not at all, we always prepare ahead of time. We communicate by email to ensure that the auditoriums or theaters are equipped to host an event since there are certain load limitations to take into account.

For example, at the Summum in Grenoble, we have a maximum number of tons per beam, and if the production team requests hanging a higher load, we have to find a compromise. In the past we set up "layered systems" or scaffolding, which was a bit different since not everything depended on the rig. Now we hang just about everything, and stage setup is planned based upon what's going on at the ceiling level.

For a traditional auditorium or theater, like Tony Garnier Hall, everything is preplanned. While we try to set up the stage based on the number spectators expected, we primarily plan the setup relative what is going on in the air, give or take a few meters. Sound systems can weigh up to five tons, so we'll never place them in a spot where the ceiling can't support the load. There are of course adjustments that often need to be made.

For big shows, we frequently hang between sixty and eighty tons, so we can't take simple half measures. We do a lot of planning and preparation ahead of time and there is no room for error, especially since we need to work quickly.

For smaller shows, where there is not a large load to hang, few trusses, not much lighting, and not much video, we are sometimes able to work everything out on site when we know the auditorium well and know that we won't face any unexpected issues."

You're working the Musiclac festival,

what are the specific aspects of this site?

"This year is pretty unique since there will be a Johnny Hallyday concert ten days before the festival and a Muse concert right after Musilac.

So we plan to set up the stage for Johnny and then leave everything in place for four days. Then Musilac will use the stage for three days, and after the festival we will probably have to make some adjustments to the structure to set up for Muse.

At festivals our days are extremely long. We sometimes have to make changes in the middle of the night to be able to use the stage and systems the next day at one in the afternoon. For a big job like this one, there are four riggers available around the clock, and in general we rotate in two-person teams."

With a work site as large and complex as this one, how are you organized technically speaking?

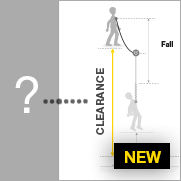

"We try to stay alert. In terms of safety, we have techniques that allow us to mitigate the risks. We always work in pairs, and we are never more than ten or fifteen meters from one another. The person on the ground has to react quickly if there is a problem."

Is everyone on your team a formally trained rigger?

Is everyone on your team a formally trained rigger?

"Rigging-specific training programs are starting to emerge. They focus primarily on hanging and distributing loads, touching less on moving around and safety.

On our team, even if we have not gone through a dedicated training program, several of us are well trained. We have either French C.A.T.S.C. certification (Certificate of Aptitude for Rope Access Work), or are state-certified climbing instructors. Among us, there are IFMGA certified high-mountain guides who have worked other professions in the mountains, and that also helps.

From time to time, we review techniques and conduct evacuation exercises.

The leading cause of accidents in rigging is fatigue. When tired, you're less attentive while handling equipment, and working non-stop can lead to forgetting to take the proper safety measures. This is why we do our best to rotate each team."

What advice would you give to someone interested in rigging?

"You need to have the passion! Rigging involves a pretty unique routine, where you alternate between periods of intense activity and laying low. My first piece of advice for someone who would like to enter the profession is to start by offering to lend a helping hand to local productions, pushing crates around, assisting a little with stage, lighting, sound, and video setup. That will allow you to see if the field is for you and if it's compatible with your lifestyle and daily routine.

If what you're really interested in is climbing, introduce yourself to local riggers. The key is to get your foot in the door. Next, training is important even if not required, and I would highly recommend having rope access skills. Completing a rigging specific training program is a plus but not required. The key to entering the field is not through training but by networking and building relationships."

What is your best work site memory?

"Probably the adrenaline rush and the satisfaction after a show with a job well done.

A few years ago we were working a show at Tony Garnier Hall for a French comedian; the team before us had set up the stage during the night. When we arrived in the morning everything was going well, and we started working on the rig. At about eleven in the morning, as we were making the final adjustments to fine tune the sound system, we could see people starting to move about down below to set up additional seating, and recounting. It turned out there was an entire section missing! The missing ten-meter deep section represented 900 seats.

Even if layer systems are a bit like LEGOS®, the setup still weights 15 tons! There were 80 to 100 of us to dismantle everything and to move the stage back 10 meters; it required precise coordination, and the adrenaline was pumping for sure. Time was also a factor since we still had to adjust the lighting and balance everything. There's a reason why we left a six-hour buffer before the auditorium opened its doors.

Once we had (re)set everything up, several people from the building said in relief, "at least we now know what we're capable of doing." Everyone was really pleased with the job well done."

Related News