Examples of dangerous carabiner loading.

A carabiner is strongest when loaded on the major axis, with the gate closed and the sleeve locked. Loading a carabiner in any other way can be dangerous.

Warnings

- Carefully read the Instructions for Use used in this technical advice before consulting the advice itself. You must have already read and understood the information in the Instructions for Use to be able to understand this supplementary information.

- Mastering these techniques requires specific training. Work with a professional to confirm your ability to perform these techniques safely and independently before attempting them unsupervised.

- We provide examples of techniques related to your activity. There may be others that we do not describe here.

Load position

Barring exceptional circumstances, a carabiner is designed to be loaded on the major axis.

Only the strength rating for the major axis with gate closed is suitable for the loads sustained by a carabiner in vertical activities.

Loading on any axis other than the major axis, and any poor positioning, will result in reduced strength.

The primary risks

Risk of unclipping

The gate can come open if:

- The carabiner is not properly closed at the time of attachment (e.g. sling caught between the nose and the gate).

- The carabiner was improperly closed or improperly locked before use and the rock, the rope or an item of equipment presses on the gate.

- The rock, the rope, or an item of equipment rubs against and unlocks the sleeve, and pushes on the gate in the direction of opening.

Risk of carabiner breakage

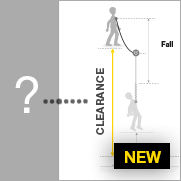

Note: Vertical practices involving a single user who is properly equipped and protected from falls rarely generate enough force to break a carabiner. However, any fall can produce an impact force that approaches the breaking strength of a poorly positioned carabiner.

Risks common to locking and non-locking carabiners

Risks of damaging the locking sleeve

Examples of risk situations in the field

1. Opening of the gate, open gate loading

Opening of the gate

> Release of the load/person

Open gate loading

> Risk of carabiner breakage

A carabiner with the gate open is weak: only 30 % of the major axis strength (e.g. 7 kN instead of 27 kN on the major axis for the Am’D).

2. Minor axis loading

A carabiner loaded on the minor axis is weak: only 35 % of the major axis strength (e.g. 8 kN instead of 27 kN on the major axis for the Am’D).

3. Multidirectional loading

The strength loss in a multidirectional load depends on the angle between the axes of loading.

4. Loading over an edge

A carabiner loaded over an edge is weak: only 30 % of the major axis strength (e.g. 6 kN instead of 23 kN on the major axis for the SPIRIT SL).

This value varies greatly depending on the position of the edge (in the middle of the gate or closer to the nose...).

5. Overloaded carabiner

The major axis strength of a carabiner is optimal when the load is closest to the spine side of the frame.

If the load shifts to the gate side, the strength is reduced.

Strength loss is most pronounced with a pear-shaped carabiner, as the nose is rather far from the spine side of the frame. Their shape also contributes to poor positioning of the load. A carabiner loaded on the gate side is weak: only 30 % of the major axis strength (e.g. 7 kN instead of 27 kN on the major axis for the WILLIAM).

6. Various cantilever loads

The different cantilever positions are too numerous to be exhaustively tested.

The strength of a carabiner in this case can be less than 30 % of the major axis strength.

A pronounced cantilever load can also damage the supporting device or anchor.

7. Pressure on the sleeve (risk of sleeve damage)

The locking sleeve is the weakest part of your carabiner.

The European standards require a sleeve strength of 1 kN under external pressure (a value easily reached in the field).

Certain standards require much higher strengths, for example 16 kN for the ANSI Z359.12 standard.