Hazardous rescues: training with GRIMP

Rescue teams from GRIMP (hazardous environment search and rescue group) receive little public attention. Made up of elite firefighters, their role is to perform rescues in difficult-to-access locations. Their typical workplace: cliffs, canyons, caves, and tall manmade structures both industrial and urban. Overall, they conducted more than 5000 rescues in 2015.

November 14 2016

Technical rescue

Rescuing a climber in Cap Canaille (Mediterranean coast, southeastern France).

Training exercises

As with all rescue units, GRIMP strives for efficiency. When lives are at stake, rescue operations must be perfectly coordinated. Education, training, simulation, and on-site drills are an integral part of their job. This is the case for two units in training that we followed: GRIMP 13 (Bouches du Rhône) and GRIMP 83 (Var). While regulations require at least one training exercise per month, the norm for these two rescue teams is usually one training exercise per week. One must take a qualifying exam to join the team or to become a team leader. For these exercises, Commander Roland Mijo, instructor at E.A.S.C. (the Applied School for Public Safety) and technical consultant in the south of France, chose two very different types of training exercises: rescuing an injured person from a construction site crane for GRIMP 83, and performing a cliff-side rescue to extract an injured climber for GRIMP 13. Each team is made up of four rescuers and a team leader. All rescues also receive support from an emergency medical team to care for the victim's injuries.

Rescue operations on a crane

Rescuing a crane operator

Once at the construction site and crane, the team leader assesses the situation. The team leader's role is to organize rescue operations, deploy the rescuers, as well as insure the safety of everyone involved and the injured person. Once the initial assessment is complete, the rescue leader moves to the base of the crane to brief the team (using a whiteboard) on the challenges, associated risks, and what is at stake for the rescue. The day's goal is to rescue an injured crane operator from the operating cabin. The team will need to ascertain whether or not the victim can be evacuated directly down the ladder or if another apparatus will be required for lowering. To determine the right maneuver, a team of two is sent to the top of the crane to attend to the injured operator. Their assessment: the victim's severe injuries combined with the steel debris at the bottom of the crane eliminate the option of lowering via the ladder. The two rescuers, in agreement with the medical team and the team leader, recommend using a rescue litter to lower the victim to the ambulance. The evacuation will place the litter in an angled position. For the most serious cases, the litter must remain horizontal. Once the green light is given, the two rescuers at the top of the crane set up the anchors and ropes that will be fixed by the two other team members on the ground. After installing the lowering system, they need to carefully place the injured operator into the litter. This step can take up to thirty minutes depending on the location and circumstances. When everything is ready, the evacuation can begin. The litter is lowered by ropes to the ambulance.

Commander Roland Mijo provides more detail, "Beyond setting up the litter, for this type of relatively standard rescue situation where the medical team remains on the ground, everything should be handled in 30 to 45 minutes. However, there are much more complex environments, and sometimes the medical team needs to directly attend to the victim. This team may be trained in vertical maneuvers… or not!"

Cliff rescue of a climber

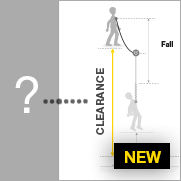

After the rescue in an industrial setting, we head to the cliffs of Cap Canaille, which tower over the Mediterranean Sea between Cassis and La Ciotat. The GRIMP 13 unit has to rescue an injured climber who is stuck at an anchor just thirty meters below the top of the route. A cliff-top rescue is one option when a helicopter rescue is not possible (98% of rescues) for a variety of reasons (no helicopter available, too windy). As in the first rescue scenario, the team leader makes an assessment of the situation, this time on rappel all the way down to the injured climber. A cliff-side rescue is determined to be the best course of action. The system is installed with a raising apparatus that allows for a direct friction-free hoist of the victim and also prevents the rescuer from banging into the cliff side. Two people descend to the anchor to place the injured climber into the litter that will be raised by the remaining team members at the top of the cliff. The two rescuers will then either ascend the rope or be raised by winch.

The rescue gear is always packed and ready!

For each of these rescue exercises, the teams travel in their rescue van. All of the requisite gear for each type of rescue is stored in the van and ready to use: ropes, winches, tripods, litters, pulleys… To save time, each rescuer climbs into the van already wearing a helmet, their personal gear, and of course a harness. In this case, a FALCON harness is an ideal choice to address the wide variety of rescue situations, offering the option of being paired with a TOP CROLL chest harness for rope ascents.

In the end, both situations are standard for hazardous environment rescue specialists. A rescue running smoothly requires the ability to skillfully execute every technique, from equipment handling to teamwork, to practicing on a regular basis. This is the reason behind each training exercise; practice makes perfect when lives are at stake.

Thank you to Commander Roland Mijo, from E.A.S.C. in Valabre, for his help.

Related News